KE LIHA PENE

- I lay down my pen -

- I lay down my pen -

This virtual exhibition forms part of an important collaboration between the Iziko Museums of South Africa and the Lesotho National Museum and Art Gallery. Showcasing Makoanyane’s work today is especially revealing thanks to the new technologies available to enhance our knowledge of the history of Samuele Makoanyane.

This exhibition is rendered using photogrammetry, which involves careful recording, measuring, and mapping of the actual sculptures, which are between 8 and 18 cm in height, into digital 3D models. Through this digitisation process, Makoanyane’s sculptures can be explored in detail and in an interactive way which would otherwise not have been possible in a physical exhibition because of the fragility of the sculptures.

Click on the play button and interact with the models using your mouse or fingers (mobile)

The curatorial team has identified figurines from the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Kirby Collection and the Social History Collections of the Iziko Museums of South Africa for display.

The portraits of traditional musicians from Lesotho, that are part of the UCT Kirby Collection of musical instruments, are accompanied by film and recordings of contemporary musicians, made on a field trip to Morija in Lesotho in early 2020.

This collaborative endeavour constitutes an important resource to clay-fired sculpture in the region and contributes to the existing body of knowledge of one of southern Africa’s greatest sculptors and story tellers.

The structure in which Samuele Makoanyane worked. (Image Source: Samuel Makoanyane by C. G. Damant. Morija Printing Works, Morija – Basutoland, 1951.)

Samuele Makoanyane grew up in the village of Koalabata in the Teyateyaneng district not far from Maseru. It was here where he began his artistic career by sculpting various animals from clay, using illustrations from school and other books as his models.

His remarkable ability to capture likenesses enabled him to travel about the country and find success wherever he went.

Following the considerable economic distress and droughts of the early 1930s in Lesotho, men were recruited to work on the Rand around Johannesburg, South Africa. Many Basotho resorted to manufacturing local crafts and traded their wares in various places within the country and across the border.

Men produced baskets, hats and other grass crafts, while women explored clay work such as pottery. Among the few exceptions, Samuele Makoanyane used clay to produce small animal models.

In addition to sculpting animals from his environment such as snakes, owls, dogs, and Indian circus elephants, Makoanyane’s choice of subject matter extended to people living in the local villages as well as historical figures.

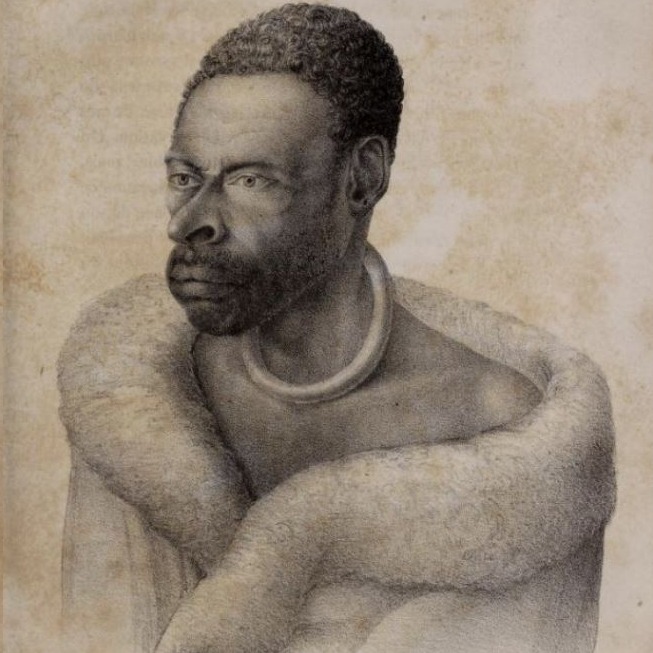

Of note is Makoanyane’s focus on warrior figures which are realistic portrayals of his great grandfather, a commanding general in King Moshoeshoe’s army. Makoanyane produced some 150 models of King Moshoeshoe and 250 models of his great grandfather. In capturing the distinct facial features of the late warrior Makoanyane, it is notable that his models appear almost identical to the facial features of his father, whom he presumably used as a model.

Makoanyane successfully navigates the up-and-coming capitalist market forces, the expatriate community, and his relationship with his advisor, agent and author of a short monograph of his life, Mr C. G. Damant, whose account served as one of the primary informants of the research into the intimacies of Makoanyane’s life.

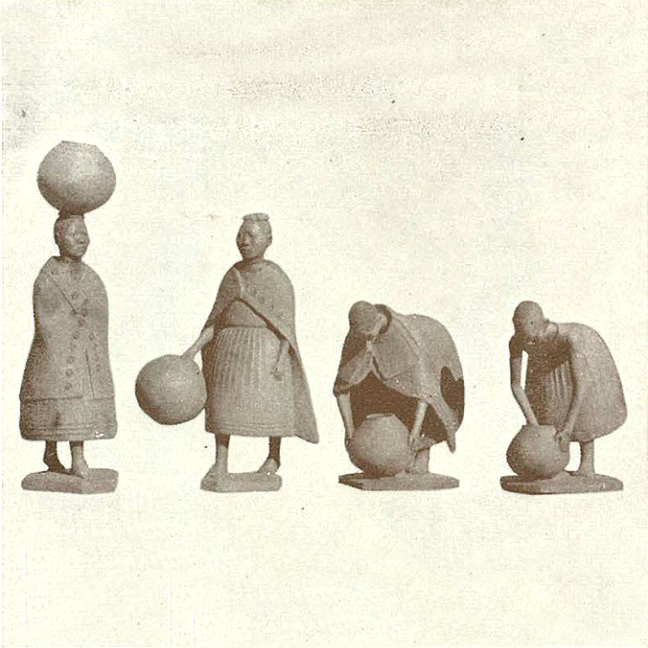

Woman with child series. (Image Source: Samuel Makoanyane by C. G. Damant. Morija

Printing Works, Morija – Basutoland, 1951.)

This partnership would prove incredibly fruitful, enabling Makoanyane’s work to grow exponentially in monetary value. Early on, Damant advised Makoanyane to rather focus on capturing the daily intricacies of people from his community rather than European figures.

The delicate size of Makoanyane’s sculptures is also due in part to Damant’s advice after Makoanyane’s bigger sculptures gave difficulties in transportation.

Woman with pot series. (Image Source: Samuel Makoanyane by C. G. Damant. Morija Printing Works, Morija – Basutoland, 1951.)

Another such instance of advice from Damant regarded some technical complications Makoanyane was having with firing his sculptures during the wintertime. Damant advised him to wait for longer periods of time between sculpting and firing to allow for moisture to dry out. However, Makoanyane was convinced that his kiln had been bewitched by someone jealous of his success. This lead him to seek a new firing pit all together.

Image of Samuele Makoanyane's great grandfather.

Damant also notes Makoanyane’s impeccably neat handwriting, citing various exchanges in Sesotho between them. Makoanyane was known for his creative use of capital letters and punctuation as well as always signing his letters off with “Ke liha pene”, which translated into English means “I lay down my pen”.

Inside Title page spread from the Book. (Image Source: Samuel Makoanyane by C. G. Damant. Morija Printing Works, Morija – Basutoland, 1951.)

Of note is how Makoanyane would always spell his name with the extra vowel at the end, which is contrary to the anglicised way in which his name has been spelt by Western scholars. It is also through these written exchanges that Makoanyane alluded to his worsening health close to his premature death at the age of 35, in 1944. It is presumed he passed away from Tuberculosis or another lung-related condition. Makoanyane was buried in his home village of Koalabata.

Woman with pot figurines. (Iziko William Fehr Collection C48, C49. Images: Nigel Pamplin)

Amongst his own people, Makoanyane’s sculptures were received with wonder. Although models were seldom showcased due to the high demand, whenever the Basotho saw them, they were in awe of his skills and intelligence. Damant accounts, however, that some regarded the works with superstition. Damant further notes, “as if they thought that Samuel’s powers were not altogether human.”

In response to his immaculate artistic abilities, Makoanyane has been quoted as saying “it was God who taught me”. He evolved a personal style which contemporaries described as “novel and out of the ordinary”. As part of Makoanyane’s process to create delicate sculptures, he strived for perfection and as a true artist, he was never satisfied with his creations, always striving after something better.

Among Makoanyane’s keen collectors was Professor Kirby of the University of the Witwatersrand. In 1935, Kirby commissioned Makoanyane to sculpt eight musical instruments and their players.

Of these, seven were completed. Makoanyane thought it beyond him to attempt the eighth, the lekhitlane player which was traditionally used in the lebollo ceremony. The reason for not completing this figurine is left unanswered.

Since his premature death at the age of 35, in 1944, Samuele Makoanyane’s fine sculptures have been hidden away in private collections and in the storerooms of museums.

Those that have been exhibited in Morija (Lesotho), Cape Town and East London, amongst others, were for the most part treated as objects of ‘cultural curiosity’ rather than revealing the nature of a unique artistic talent that emerged out of a small village in Lesotho, Koalabata.

In extending this intimate engagement with the sculptures, these figures will also be showcased and given prominence in the new Lesotho National Museum and Art Gallery to open in Maseru in 2022, meanwhile, two of Makoanyane’s sculptures are available for viewing at the Castle of Good Hope as part of the Iziko William Fehr Collection.

There is much to be discovered about Samuele Makoanyane, his knowledge of ceramics, his use of visual and historic sources and his ability to capture the likenesses of his immediate community.

The process behind how these sculptures were made, stored, dried and fired remains largely unknown however it is presumed they were either placed on the surface of the ground, or placed in a shallow pit, covered with sticks and fired.

With further research into the depths of Makoanyane’s life and practice and through this ongoing exhibition project, some of these questions may yet be answered.

Having interacted with the sculptures, it is noticeable that some of them have been damaged, broken, or repaired. This is a common issue in conservation and restoration which we wish to address further in the coming iterations of the project.

All the 3D models exhibited in this virtual exhibition are hosted by Sketchfab. Click here to view the collection.

A field trip to the Morija Museum and Archives was undertaken in 2020, where this was further explored. A series of recordings and a film was made of five out of the seven instruments Makoanyane sculpted.

Damant, C.G. 1951. Samuel Makoanyane. Morija Sesuto Book Depot, p. 6-17.

Dreyer, J. 1999. Samuel Makoanyane (1909-1944) – ceramic artist from Koalabata, Lesotho. South African Journal of Ethnology, 22(1):32-38.